I have been playing Frisketball since 2011 when a bunch of Paideia Juniors and I made it up after our season ended in the spring. We could only get a handful of people, and didn't want to drive out to a field or put on cleats. So we needed something akin to pickup basketball where you could almost always play (on the same field) and people could come and go with little disturbance to the overall game. Frisketball was created and is best played with between 4 and 8 players.

The rules started almost identical to Hot Box. The playing field is the basketball court. The goal is to complete a pass to your team inside of the paint. That is it. Super simple.

In the past few years we have evolved the rules a little bit, making the game more like basketball and finding other tweaks. Here are the basic rules that we always play with.

- Stall is 7

- Picks are discouraged, but so is calling picks

- Neither offense nor defense can stand in the paint for more than 3 seconds

- If you throw the disc in the hoop it is a goal (good luck)

- Double-teams are allowed

The game is all about shifting spaces and the rectangular nature of the goal makes scoring interesting. It is a game that encourages fast play, creative throws, and offering appropriate help defense.

A 2-on-2 game is hard because the defense will always play towards the paint and with only one other person as a viable target it becomes difficult to find useful attacking space (but there is plenty of reset space).

A 3-on-3 game is exciting because there can be lots of swinging to shift attack angles, but there still aren't enough people for you to rest too much.

A 4-on-4 game is tough because the defense can clog so effectively. The offense needs to be much more coordinated, which can be very rewarding.

The game can also be full or half-court depending on numbers and available space.

A few of the alternate rules that we have installed in the game:

- No over-and-back: in a full court game once the thrower establish one point of contact beyond the half-court line if they go backwards (either with a pivot or a pass), it is a turnover.

- Out of bounds: if any point of contact for the thrower is on or beyond the out of bounds line it is a turnover. This includes stopping with the disc after you catch it (it also creates interesting trap situations on defense).

- 10 second rule: in a full court game the offensive team has 10 seconds (from in-bounds possession of the disc) to get the disc past the half-court line. This 10 seconds can be counted by anyone on or off the field, and must be counted down from 10 to avoid confusion with the stall

- 2 point line: in a full court game, if a goal is thrown from beyond the half-court line it is worth two points

- Jump ball: in a full court game, to start the game you can have a jump ball at center court. If the disc hits the ground without being caught then the team going away from the side where it lands starts with the disc at its current location.

Frisketball is really tremendous fun. People who are bad at ultimate can still be good at frisketball. It is easy to play with all ages and across gender. It isn't a lot of running, but is incredibly tiring. It can be physical or gentle depending on how you want to play it. If you give it a go and have feedback please don't hesitate to post it as a comment. All of those expanded rules were the rules of just having fun with it, so more collaboration is encouraged.

Welcome. This site primarily is concerned with coaching ultimate and ultimate strategy, but over the years we’ve discussed just about anything involving running after a piece of plastic.

Friday, June 24, 2016

Wednesday, June 01, 2016

Stupid Games (part 2: BruteBall?)

Ok, I've got a few tweaks to scrimmages lined up, but since it has been almost a month since my last post I'll go with something that is more unique. I cannot claim credit for this game. At best I could give credit to Noah Cohen, but I think he learned it from someone in North Carolina. Patrick Hard went to school in NC, so let's pretend he invented it.

The game's name is still up in the air. Noah called it "honey pot" . . . I am not calling a game that I might be teaching middle school kids by that name. From now on I will refer to it as BruteBall (please someone leave a better name in the comments).

The game feels similar to KanJam in that there is a can (in this case a larger, circular trashcan). But unlike KanJam it isn't a passive game about throwing and deflection. It also isn't symmetric. The game is played with exactly 3 players. Each possession two are on offense and one is on defense. The offenders are trying to put the disc in the trashcan in pretty much any manner they can, but the disc can't cross the plane at the top of the lid while it is still in someone's hand. So you literally can't jam the can.

Like ultimate, you can't travel when you have the disc and you have a stall (in this case 6 seconds). But unlike ultimate, the defender doesn't have to mark in order to stall. You would think that scoring happens when the offense puts the disc in the can, but that isn't the case. Each possession, a point is scored for the defender if there is a turnover. Then the defender rotates to a new person and you start a new possession. The only rules for the defender are they they cannot cover the can with their body/arms. Games are played to whatever you like, but 5 seems to work pretty well.

To start a possession the defender just tosses the disc somewhere in the playing area and the game starts. The playing area can be as large as you like, but must completely surround the can. It doesn't have to be a circle where the can is the center, but the can needs to be accessible from all sides.

So what is this game about. It might seem like the thing to do defensively is to just sit at the can. There are no rules preventing you from doing that, but it will allow the offense to get really close to the can, and then it only takes the offender getting the disc around your body and dropping it in to score. You might logically think that the thing to do is to stall while playing tight defense on the other offender. But then you leave an uncontested throw for on offender and if the other one sneaks past you then it is an easy goal.

Instead the thing to do is to figure out the balance between the two. You play the lane to block a direct shot while trying to also contest a pass to the other offender, all while stalling. So this game is working on help defense and controlling angles (I guess . . . it is mostly just fun).

That is it for another installment of Stupid Games. I'll come back next month with something else . . . maybe with pictures.

The game's name is still up in the air. Noah called it "honey pot" . . . I am not calling a game that I might be teaching middle school kids by that name. From now on I will refer to it as BruteBall (please someone leave a better name in the comments).

The game feels similar to KanJam in that there is a can (in this case a larger, circular trashcan). But unlike KanJam it isn't a passive game about throwing and deflection. It also isn't symmetric. The game is played with exactly 3 players. Each possession two are on offense and one is on defense. The offenders are trying to put the disc in the trashcan in pretty much any manner they can, but the disc can't cross the plane at the top of the lid while it is still in someone's hand. So you literally can't jam the can.

Like ultimate, you can't travel when you have the disc and you have a stall (in this case 6 seconds). But unlike ultimate, the defender doesn't have to mark in order to stall. You would think that scoring happens when the offense puts the disc in the can, but that isn't the case. Each possession, a point is scored for the defender if there is a turnover. Then the defender rotates to a new person and you start a new possession. The only rules for the defender are they they cannot cover the can with their body/arms. Games are played to whatever you like, but 5 seems to work pretty well.

To start a possession the defender just tosses the disc somewhere in the playing area and the game starts. The playing area can be as large as you like, but must completely surround the can. It doesn't have to be a circle where the can is the center, but the can needs to be accessible from all sides.

So what is this game about. It might seem like the thing to do defensively is to just sit at the can. There are no rules preventing you from doing that, but it will allow the offense to get really close to the can, and then it only takes the offender getting the disc around your body and dropping it in to score. You might logically think that the thing to do is to stall while playing tight defense on the other offender. But then you leave an uncontested throw for on offender and if the other one sneaks past you then it is an easy goal.

Instead the thing to do is to figure out the balance between the two. You play the lane to block a direct shot while trying to also contest a pass to the other offender, all while stalling. So this game is working on help defense and controlling angles (I guess . . . it is mostly just fun).

That is it for another installment of Stupid Games. I'll come back next month with something else . . . maybe with pictures.

Wednesday, May 04, 2016

Stupid Games (part 1: 4v6)

I wonder how many multi-part posts I can start before I finish any of them?

I like playing games, and I like making games. It is one of the things that I really enjoy about coaching. Finding the right tweak or an existing drill (or whole-cloth new drill) to teach the specific thing you are trying to get at is a ton of fun.

One game that we created is called 4v6. I'd make a diagram of it, but the diagram is incredibly boring. 4v6 is played in a box of four cones approximately 10yds by 12 yds. The team of six is on "offense" and is simply trying to keep the disc alive (no turnovers). The team of four is on "defense" and is trying to generate as many turns as possible. The game is played for a short amount of time (5 minutes) where the offensive team is always on offense. In the event of a turn, the disc goes back to the offensive team. The defense scores one point for each turnover. After the 5 minutes is over the two teams switch and the second defensive team tries to beat the first defensive team's score.

The stall is 5, but you don't have to be marking to stall the person with the disc. All offensive players must have one point of contact with the ground at all times. This basically means no running or jumping. The defensive team does not have this restriction. This really helps because the defensive team can "guard" four of the five non-throwing offensive players and can run to get the fifth.

A few other rules/tweaks we have tried:

-Have two teams of four and keep two people as permanent offense.

-No patty-cake rules where you can't throw back to the person who threw to you unless the count is over three (basically no back and forth with another player)

-Changing the size of the box. This really matters depending on disc-skill and athleticism. With Chain I had to use a larger box because the defenders were so fast.

-Changing the number of players. Really the game should be called "N+2" because the offense should always have two extra players. That means the defense can't shut down everyone and has to work together to cover the extra open offender.

If anyone still reads this blog and has questions, comments or suggestions about this game please don't hesitate to leave them below. 4v6 is far from perfect, but it does work on some good ultimate skills in a focused fashion.

I like playing games, and I like making games. It is one of the things that I really enjoy about coaching. Finding the right tweak or an existing drill (or whole-cloth new drill) to teach the specific thing you are trying to get at is a ton of fun.

One game that we created is called 4v6. I'd make a diagram of it, but the diagram is incredibly boring. 4v6 is played in a box of four cones approximately 10yds by 12 yds. The team of six is on "offense" and is simply trying to keep the disc alive (no turnovers). The team of four is on "defense" and is trying to generate as many turns as possible. The game is played for a short amount of time (5 minutes) where the offensive team is always on offense. In the event of a turn, the disc goes back to the offensive team. The defense scores one point for each turnover. After the 5 minutes is over the two teams switch and the second defensive team tries to beat the first defensive team's score.

The stall is 5, but you don't have to be marking to stall the person with the disc. All offensive players must have one point of contact with the ground at all times. This basically means no running or jumping. The defensive team does not have this restriction. This really helps because the defensive team can "guard" four of the five non-throwing offensive players and can run to get the fifth.

A few other rules/tweaks we have tried:

-Have two teams of four and keep two people as permanent offense.

-No patty-cake rules where you can't throw back to the person who threw to you unless the count is over three (basically no back and forth with another player)

-Changing the size of the box. This really matters depending on disc-skill and athleticism. With Chain I had to use a larger box because the defenders were so fast.

-Changing the number of players. Really the game should be called "N+2" because the offense should always have two extra players. That means the defense can't shut down everyone and has to work together to cover the extra open offender.

If anyone still reads this blog and has questions, comments or suggestions about this game please don't hesitate to leave them below. 4v6 is far from perfect, but it does work on some good ultimate skills in a focused fashion.

Saturday, April 30, 2016

Statistics Update, and a note on subbing patterns

I really should be working on the cutting tree, but with my coaching future in question and the high school season in full swing I have tabled that to work on some other things.

I have continued collecting data on what I think is are some novel statistics. After a year of tracking these things, I have actually gotten a somewhat reasonable set of data and I feel like conclusions can start to be made.

The first one I've talked about before: it is percentage of possessions that result in an unforced error (%UE). Conceptually this is "bad," but not necessarily directly correlated with score. In a windy game the %UE might go up very high, even if the teams are really good. Unlike "breaks" or "offensive efficiency," you can lose a game where you have a better %UE. Categorizing %UE is a little subjective, but I have been using the rule of if the defense gets a hand on it then it was "forced." Everything else falls in "unforced" and is counted. Paideia's average %UE for the season so far is ~47%, which is pretty good. Basically we give up the frisbee just under half of the time we have it . . . sounds bad, but when compared to individual games where the number is 60+% this is fine.

Since I had enough data to try this, I have wondered what this does correlate with. Anecdotally we would assume that this correlates with wins because the lower your %UE the less you are "screwing up." But I decided to take it one step farther and run a correlation with the final point differential of the game. As I get more games I have been updating the data, and it currently has an R^2 value of 0.385. Honestly I don't know if that is "good," and everything I read tells me that just looking at the R^2 value isn't enough to deem good or bad anyway. But the important thing that I note is how that number goes up. In general, aside from the data collected at a windy tournament, the correlation coefficient is getting larger as I enter more games and we play in more tournaments. I'll keep taking the data, and seeing if %UE is actually a reasonable indicator of team success (without being trivial because it IS team success . . . looking at you "breaks").

I also have continued to play around with number of possessions per goal (PPG). There isn't as much useful data there. I have lots of good number for my team, including a drubbing by Amherst where we played well (-9, but a good -9) and had a 6.2 and a horrible game against Grady (-2, but we played like shit) and also had a 6.2. PPG isn't useful in a single game because it is just the score. If you win PPG you won that game. But I am curious if in general teams with lower average PPGs beat opponents with larger average PPGs. In order to figure that out we would need more data from multiple teams, not just the data from one.

Lastly I have started using the score sheets from the past two years worth of Paideia games to build a win probability matrix. Basically my win probability (WP) is the likelihood of the team with X winning when the score is X-Y. To expand this beyond one team I had the volunteers for Paideia Cup track the order of scores so they could be entered. So far the only parameter of win probability that is being tracked is current score state, but eventually with enough data it might be expanded to more parameters. The goal is to be able to figure out which points are, on average, important. Anecdotally, after a few games were entered, the likelihood of winning games when you were up 9-7 was 0% (again, only a few games) and if you were ahead 10-6 it was 100%. That means at 9-6 this point "really matters" and maybe it is worth brining in your best players. Obviously those numbers will change when more games are entered, which is what I am doing for much of May.

Impact on subbing patters is the end goal of WP is to help me inform subbing patters. I did something similar last year and it made me realize that leaving our "best" players on the field for three points was a waste. I've used that to adopt a subbing style that keeps people rested, gives new players more responsibility and hopefully bends development curves upwards with a goal of stabilizing the 4 year sinusoidal graph that is "team quality." But using that pattern had gotten us four straight losses to in-town rival Grady High School. We knew we would play them in the State Championship so we practiced and implemented a different subbing pattern that looked more like a club/college offense/defense system. We won all of our games by 9+ en route to a state championship.

I don't want to use that system all of the time, because it means some people are never on the field for an offensive point, and I think that hurts their development. But having that information is interesting when coupled with WP numbers. Maybe there is a time when a shift happens from a more team oriented subbing pattern to a more success driven pattern? Figuring out when that switch should happen feels just as valuable as figuring out that our "best" players have a terrible conversion rate when they have been on the field for 3 points.

I have continued collecting data on what I think is are some novel statistics. After a year of tracking these things, I have actually gotten a somewhat reasonable set of data and I feel like conclusions can start to be made.

The first one I've talked about before: it is percentage of possessions that result in an unforced error (%UE). Conceptually this is "bad," but not necessarily directly correlated with score. In a windy game the %UE might go up very high, even if the teams are really good. Unlike "breaks" or "offensive efficiency," you can lose a game where you have a better %UE. Categorizing %UE is a little subjective, but I have been using the rule of if the defense gets a hand on it then it was "forced." Everything else falls in "unforced" and is counted. Paideia's average %UE for the season so far is ~47%, which is pretty good. Basically we give up the frisbee just under half of the time we have it . . . sounds bad, but when compared to individual games where the number is 60+% this is fine.

Since I had enough data to try this, I have wondered what this does correlate with. Anecdotally we would assume that this correlates with wins because the lower your %UE the less you are "screwing up." But I decided to take it one step farther and run a correlation with the final point differential of the game. As I get more games I have been updating the data, and it currently has an R^2 value of 0.385. Honestly I don't know if that is "good," and everything I read tells me that just looking at the R^2 value isn't enough to deem good or bad anyway. But the important thing that I note is how that number goes up. In general, aside from the data collected at a windy tournament, the correlation coefficient is getting larger as I enter more games and we play in more tournaments. I'll keep taking the data, and seeing if %UE is actually a reasonable indicator of team success (without being trivial because it IS team success . . . looking at you "breaks").

I also have continued to play around with number of possessions per goal (PPG). There isn't as much useful data there. I have lots of good number for my team, including a drubbing by Amherst where we played well (-9, but a good -9) and had a 6.2 and a horrible game against Grady (-2, but we played like shit) and also had a 6.2. PPG isn't useful in a single game because it is just the score. If you win PPG you won that game. But I am curious if in general teams with lower average PPGs beat opponents with larger average PPGs. In order to figure that out we would need more data from multiple teams, not just the data from one.

Lastly I have started using the score sheets from the past two years worth of Paideia games to build a win probability matrix. Basically my win probability (WP) is the likelihood of the team with X winning when the score is X-Y. To expand this beyond one team I had the volunteers for Paideia Cup track the order of scores so they could be entered. So far the only parameter of win probability that is being tracked is current score state, but eventually with enough data it might be expanded to more parameters. The goal is to be able to figure out which points are, on average, important. Anecdotally, after a few games were entered, the likelihood of winning games when you were up 9-7 was 0% (again, only a few games) and if you were ahead 10-6 it was 100%. That means at 9-6 this point "really matters" and maybe it is worth brining in your best players. Obviously those numbers will change when more games are entered, which is what I am doing for much of May.

Impact on subbing patters is the end goal of WP is to help me inform subbing patters. I did something similar last year and it made me realize that leaving our "best" players on the field for three points was a waste. I've used that to adopt a subbing style that keeps people rested, gives new players more responsibility and hopefully bends development curves upwards with a goal of stabilizing the 4 year sinusoidal graph that is "team quality." But using that pattern had gotten us four straight losses to in-town rival Grady High School. We knew we would play them in the State Championship so we practiced and implemented a different subbing pattern that looked more like a club/college offense/defense system. We won all of our games by 9+ en route to a state championship.

I don't want to use that system all of the time, because it means some people are never on the field for an offensive point, and I think that hurts their development. But having that information is interesting when coupled with WP numbers. Maybe there is a time when a shift happens from a more team oriented subbing pattern to a more success driven pattern? Figuring out when that switch should happen feels just as valuable as figuring out that our "best" players have a terrible conversion rate when they have been on the field for 3 points.

Thursday, February 18, 2016

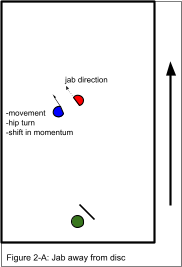

The Cutting Tree: 2 - Jab Cut

This is an excerpt of a larger document detailing the 9 branches of the cutting tree. It is not a finished product, but I am putting it here to work on formatting and field any comments people have.

Jab Cut - The jab cut is done by making a jabbing motion typically in a lateral direction to your frontal plane. This creates the illusion of running in that direction, while it also loads your leg to push and move in the opposite direction. In this move you are trying to exploit your defender’s tendency to (over)react to your movement and put them in a weak-reaction state. As a result it is important to think about the purpose and placement of your jab in terms of your defender.

Placement of the jab (especially the 45-degree jab) with respect to the outside foot of your opponent is also important. A placement outside the space between the defender’s feet (footbox) will likely create a drop-step or a hip-turn. A placement inside the footbox will likely create a backpedal.

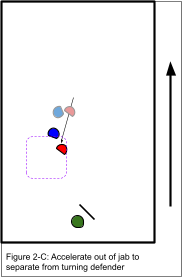

The last, most important component of the jab step is the acceleration out of the step. It is your acceleration out of the jab that creates a majority of your separation. The jab is simply reducing the reaction of your defender, allowing you to start your acceleration before they can react. Loading your jab foot properly, and being able to generate force from that in the desired direction allows you to get separation from your defender.

Here are some examples of a jab cut:

![]()

![]()

![]()

A note about the last cut: it isn't very effective. The cutter gets open, and gets the disc, but because they are in front of their defender their jab didn't really change the defender's reaction before motion. In the first two the jab is perpendicular to the defender's frontal plane (first video is into the frontal plane and the second video is away) causing the defender to generate momentum perpendicular to their frontal plane and in the wrong direction.

This one shows a double-jab (which is still a jab) more parallel to the frontal plane of the defender and causing a hip-turn.

![]()

Jab Cut - The jab cut is done by making a jabbing motion typically in a lateral direction to your frontal plane. This creates the illusion of running in that direction, while it also loads your leg to push and move in the opposite direction. In this move you are trying to exploit your defender’s tendency to (over)react to your movement and put them in a weak-reaction state. As a result it is important to think about the purpose and placement of your jab in terms of your defender.

- A jab is meant to generate a hip-turn, pause, or weight-shift by your defender.

- A jab towards the frontal plane of your defender will possibly generate a back-step.

- A jab along the frontal plane of your defender may generate a hip turn, but it also might cause the defender to shuffle and maintain their positioning.

- A jab at a 45 degree angle to their frontal plane (an attacking jab) will force a clear hip turn. At worst, assuming the defender absorbs it well, it will generate a hop backwards.

Placement of the jab (especially the 45-degree jab) with respect to the outside foot of your opponent is also important. A placement outside the space between the defender’s feet (footbox) will likely create a drop-step or a hip-turn. A placement inside the footbox will likely create a backpedal.

The last, most important component of the jab step is the acceleration out of the step. It is your acceleration out of the jab that creates a majority of your separation. The jab is simply reducing the reaction of your defender, allowing you to start your acceleration before they can react. Loading your jab foot properly, and being able to generate force from that in the desired direction allows you to get separation from your defender.

A note about the last cut: it isn't very effective. The cutter gets open, and gets the disc, but because they are in front of their defender their jab didn't really change the defender's reaction before motion. In the first two the jab is perpendicular to the defender's frontal plane (first video is into the frontal plane and the second video is away) causing the defender to generate momentum perpendicular to their frontal plane and in the wrong direction.

This one shows a double-jab (which is still a jab) more parallel to the frontal plane of the defender and causing a hip-turn.

Monday, February 15, 2016

The Cutting Tree: Introduction

A few years ago, on Skyd, Mike "MC" Caldwell wrote an article titled "The Cutting Tree." My excitement was through the roof, as the implied cutting tree surely was like a football cutting tree and it would not only allow for common vernacular but be a coaching tool that could truly improve youth development. I wrote a post about it then and mentioned that Kyle and I would be working on something. Well, two years have passed and while I haven't been working on that exclusively, I have made some progress and think it is time to start putting this out. So here is a rough introduction to what will hopefully be a discussion about cutting as a skill.

And that is that. There are nine sections to the tree. Currently I am going through video trying to find more examples of each cut. Diagrams and descriptions are mostly written, and might end up here in a piecemeal fashion. At some point I will probably get Ultiworld to publish it if I think it is ready. By no means am I doing this alone. Kyle Weisbrod, Miranda Knowles, Jason Simpson and Andy Loveseth have all been asked for their opinions and their contributions have been incredibly informative. Originally the "tree" was a scattered mess, which is exactly the opposite of its purpose. Also I need to thank my wife for proof-reading this and helping me not sound like an idiot despite my best efforts.

Welcome to the Cutting Tree. This is an attempt to codify a language for cutting so that coaches can better develop training programs to create superior cutters. One problem that slows development in our sport is that we often lack a common language set, especially across regions. This leads to lost time as players/coaches have to explain what they mean to each other before real understanding can be achieved. Think of the number of times you have drawn out what a “question mark cut” is to another player.

That said, here's what this is not. I am not advocating for teams to lose their special vernacular. Calling an upline cut a beta, shooter or power cut is fine. But I think being able to trace those names back to a common motion helps development. Additionally, this is by no means a tutorial for how to cut effectively. That will take tons of practice using methodologies that are not described here. Rather the following is a set of practicable tools that a cutter can use on the way to being more effective.

First we should define “cut” for the sake of this article. From here on when I refer to a “cut” I am talking about a specific pattern of movement (feet, legs and momentum) designed to get separation from a defender. All of these cuts will not get the same type of separation in all different situations and against different styles of defense. But the purpose of developing this language is so that we (as coaches) can more easily discuss movement against a defender and what type of cuts make sense in a particular offensive scheme or situation.

There is a tendency while reading this to want to refer to particular, situational cuts. Above, the “up line” cut was referenced as an example even though it doesn't fi our criteria for a "cut." The “up line” cut is not mentioned again in this document because it is situational (the location of the disc, offender and force are required). Instead the following breaks down and names the possible ways to execute an upline cut. You might gain separation from your defender using the same method for different situational cuts (continuation, scoring, etc.). The hope is that by naming these methods for gaining separation we might also be able to better train the right method for the right situation (something that is already done at many clinics and in many huddles).

There are a total of 9 different cuts described here. The differences in the cuts are at times minimal, and one could argue that some of them should be collapsed into one cut. On the other hand some would argue that there are other cuts that aren’t described in this document that should be included. Both stances are correct on some level, but it is important to remember that this isn’t a definitive guide but rather the start of a conversation.

Here are the 9 cuts:

1 - Straight Cut

2 - Jab Cut

3 - Check Cut

4 - Double Cut

5 - Press Cut

6 - Seal Cut

7 - Elbow Cut

8 - Slice Cut

9 - Cross CutAnd that is that. There are nine sections to the tree. Currently I am going through video trying to find more examples of each cut. Diagrams and descriptions are mostly written, and might end up here in a piecemeal fashion. At some point I will probably get Ultiworld to publish it if I think it is ready. By no means am I doing this alone. Kyle Weisbrod, Miranda Knowles, Jason Simpson and Andy Loveseth have all been asked for their opinions and their contributions have been incredibly informative. Originally the "tree" was a scattered mess, which is exactly the opposite of its purpose. Also I need to thank my wife for proof-reading this and helping me not sound like an idiot despite my best efforts.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)